Advancing Health Equity for Intersex Individuals: Archived from U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health

📢 Disclosure Statement

This article contains republished content originally provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The information has been preserved in its entirety to maintain access to critical public health guidance.

🔹 Why are we republishing this? Due to recent federal policy changes, some CDC materials on sexual and reproductive health have been removed or altered. We are committed to ensuring that evidence-based, medically accurate resources remain publicly available.

🔹 Disclaimer: This content is not modified from its original version. However, as science evolves, we encourage readers to verify information with trusted medical sources or consult healthcare professionals for the most up-to-date recommendations.

Evidentia Sexual Health Education Center is an independent organization and does not represent or imply endorsement by the CDC or any government entity.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health

JANUARY 2025

DISCLAIMER

Listings of any nonfederal resources are not all-inclusive. Nothing in this document constitutes a direct or indirect endorsement by OASH or HHS of any nonfederal entity’s products, services, or policies, and any reference to nonfederal entity’s products, services, or policies should not be construed as such.

PUBLIC DOMAIN NOTICE

All material appearing in this publication is in the public domain and may be reproduced or copied without permission from OASH. Citation of the source is appreciated. However, this publication may not be reproduced or distributed for a fee without the specific, written authorization of OASH.

ELECTRONIC ACCESS AND PRINTED COPIES

This publication may be downloaded at www.hhs.gov/programs/topic-sites/lgbtqi/index.html. RECOMMENDED CITATION

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health (OASH: Advancing Health Equity for Intersex Individuals. Washington, DC: Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health. November 2024.

ORIGINATING OFFICE

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health. 200 Independence Avenue SW, Washington, DC 20201. Released November 2024.

NONDISCRIMINATION NOTICE

The Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health (OASH complies with applicable Federal civil rights laws

and does not discriminate on the basis of race, ethnicity, color, national origin, age, disability, religion, or sex (including pregnancy, sexual orientation, gender identity, and sex characteristics. OASH does not exclude people or treat them differently because of race, color, national origin, age, disability, religion, or sex (including pregnancy, sexual orientation, gender identity, and sex characteristics).

Released January 2025

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Like all Americans, the over 5 million intersex people in our nation deserve to live healthy and fulfilling lives free from stigma and discrimination. This report uses the term intersex as an umbrella term to refer to people born with differences or variations in their sex characteristics or reproductive anatomy. Yet intersex people in the United States and around the world face significant health disparities and barriers to achieving health equity. Over the past decades, a growing body of evidence and advocacy by intersex people has demonstrated that current medical practices for intersex patients, especially children, can cause lifelong harm and must be reevaluated.

To help address these health disparities, the Department of Health and Human Services is releasing this first of its kind report on advancing health equity for intersex individuals. This report is the result of a historic series of listening sessions with intersex individuals, advocates, and health care providers about their expertise and lived experiences. This report aims to provide a roadmap for a whole-of-society approach to advance health equity for intersex individuals by bringing together policymakers, health care providers, intersex advocates, parents and families, and community leaders. This report also aims to increase awareness among health care providers, patients, and families about the harms of some current medical practices for intersex patients and share promising practices for advancing health equity for intersex people. Achieving health equity for intersex people will require partnership, outreach, and education to patients, families, and providers, as well as changes to laws and policies.

The intersex community is diverse, and each intersex person has a different story and lived experience. Intersex people are artists and advocates, innovators and scientists, teachers and community leaders, parents, and family members. While no two intersex people are the same, sadly too many intersex people have experienced common forms of stigma and trauma because of the lack of access to affirming health care and barriers to health equity. This is especially true for intersex people with intersectional identities, including intersex people of color and intersex people with disabilities. Even as this report acknowledges the pervasive barriers intersex people face in our society and health care system, it makes clear that, when intersex people are affirmed and receive high-quality care, they can thrive.

Like all Americans, the over 5 million intersex people in our nation deserve to live healthy and fulfilling lives free from stigma and discrimination.

While no two intersex people are the same, sadly too many intersex people have experienced common forms of stigma and trauma because of the lack of access to health care they need and barriers to health equity. This is especially true for intersex people of color and intersex people with disabilities.

Section 1 of this report provides an overview of the language we use to discuss intersex people and intersex health. Approximately 1.7 percent of people worldwide are intersex (Fausto-Sterling, 1993; T. Jones, 2018), or approximately 136 million people worldwide and 5.7 million people in the US (U.S. Census Bureau, 2023)1. Intersex variations are a natural component of human diversity.

Section 2 summarizes the significant barriers to health equity that intersex Americans face during childhood and adulthood. Healthy People 2030, a federal initiative to improve health and well-being over the next decade, defines health equity as “the attainment of the highest levels of health for all people.” Many intersex Americans struggle to achieve health equity. Key barriers include the ongoing practice of performing non-emergent, non-consensual surgeries in intersex infants which research shows can cause long-lasting harm. In addition, few health care providers receive adequate training to provide affirming and high-quality care to intersex patients. Other systemic challenges in our health care system – such as lack of intersex inclusion in most medical record systems, treatment protocols, and insurance claim systems – can lead to increased risks of improper care and adverse health outcomes. Many intersex individuals also face trauma and medical mistrust because of their experiences receiving health care that was not affirming.

Section 3 discusses promising practices for advancing health equity for intersex individuals. It also highlights the need for new approaches to intersex care, with an emphasis on supporting the health of intersex people across the lifespan. Equitable and inclusive health care, family acceptance, and social support can make a profound difference in the lives of intersex people, supporting their ability to thrive.

Finally, Section 4 provides a set of guiding principles for action to advance health equity for intersex people. It recognizes that achieving health equity for intersex people will require a whole-of-society approach, including through actions to ensure informed consent as a guiding value for all health policies; develop an intersex-affirming research agenda that expands data collection to improve patient outcomes; strengthen provider training to support access to high-quality care; promote family acceptance for intersex individuals; and empower the leadership of people with lived intersex experience.

This report constitutes HHS’s first report on health equity and intersex populations.

It was developed through review of best available science and evidence, including qualitative data collection, a comprehensive scoping review, and input from a range of respondents including intersex people, their families, health care professionals, and medical associations. Intersex people and community-led groups were consulted and directly involved throughout the development of this report. As HHS strives toward patient-centered approaches to health care, the inclusion of people with lived experiences provides a critical foundation.

In this report, HHS seeks to center the health and wellbeing of intersex people themselves and offer recommendations that prioritize their maximum wellbeing.

Note: The U.S. Census Bureau citation is for total U.S. and world population figures as of October 20, 2023. Approximate populations of intersex people are calculated based on these total population figures and the intersex variation prevalence estimate from Fausto-Sterling (1993) and T. Jones (2018).

SECTION 1

TERMINOLOGY AND IDENTITY

This report uses the term intersex as an umbrella term to refer to people born with differences or variations in their sex characteristics or reproductive anatomy. The term intersex also refers to an identity and community – the “I” in LGBTQI+ – though some people with these traits do not explicitly identify as intersex.

The intersex community is diverse, and each intersex person has

a different story and lived experience. While intersex individuals cannot be reduced to their medical experiences and physical traits, it’s important for health care providers, policymakers, and family members to understand several key terms about sex variation that impact health care experiences of intersex individuals:

Sex Characteristics

Sex characteristics commonly refer to seven physical traits directly or indirectly related to reproduction, which are either present from birth (primary sex characteristics) or develop during puberty (secondary sex characteristics) (Richards & Hawley, 2011). These seven traits are sex chromosomes, gonads, external genital structures, internal structures, sex hormone production, sex hormone response, and secondary sex characteristics. Human sex characteristics exhibit considerable variation, both in their individual manifestation and in the combinations in which they present. As an umbrella term, intersex refers to individuals who have sex characteristics present at birth or which develop naturally during puberty that demonstrate substantial variation in at least one of these seven physical traits (Carpenter, 2018).

Sex Characteristic Variations

There are more than 40 named variations that fall under the intersex umbrella, as well as unnamed variations of sex characteristics where the origin of the variation is unknown (Carpenter, 2018). The National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) has published a list of medical conditions that are often considered as intersex (Committee on Measuring Sex, Gender Identity, and Sexual Orientation et al. 2022, page 150). Some of the most common intersex variations include Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia (CAH), Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome (AIS), Klinefelter Syndrome, Turner Syndrome, and hypospadias. As a result of complex genetic and developmental contributors, individuals who have the same intersex variation may differ substantially in their physical traits and medical needs.

Intersex variations are most commonly identified at birth or during puberty, but it is also not uncommon for adults to discover they have intersex traits while seeking fertility care (Terribile et al., 2019) or through unrelated medical procedures (Patil et al., 2013). While many intersex individuals may require specialized health care, for many intersex people, their variations in sex characteristics are a healthy part of human diversity and do not pose any threats to overall health (Reis, 2022). Nevertheless, many intersex individuals report facing medical interventions because their variations in sex characteristics have been treated as a medical disorder.

The term intersex is not synonymous with transgender or nonbinary. Transgender refers to people whose gender identity (e.g., man, woman, nonbinary) does not align with their sex assigned at birth, whereas intersex refers to variation in a person’s sex characteristics. These terms are not mutually exclusive, as some intersex people may also identify as transgender or nonbinary.

The intersex community is diverse, and each intersex person has a different story and lived experience.

SECTION 2

BARRIERS TO HEALTH EQUITY FOR INTERSEX INDIVIDUALS

While intersex variation is a natural part of human diversity, intersex variation has historically been treated as a medical disorder rather than as just one more component of human physical variation. Historic and current medical practices have often focused on surgical interventions on infants to change their sex characteristics to conform with a single sex, rather than the health care needs of the intersex individual.

“I knew people

were working really

hard to fix me, but

that’s all I was—a

problem that needed

to be fixed. I thought of myself

as a problem that needed to be fixed—that’s rammed in my psyche. [Because of this belief,] I have enormous trust issues. It’s a huge thing to think that you’re not worthy of real care at all.”

Source: email input from anonymous listening session participant

Research and advocacy from intersex individuals has documented that non-consensual, medically unnecessary interventions for intersex infants can cause lifelong harm. These interventions impact people into adolescence and adulthood, and intersex adults face significant barriers in accessing high- quality care that affirms and meets their needs.

This section will first discuss the barriers to health equity that intersex infants and children face, and the growing evidence that surgical interventions on intersex infants can cause lasting harm, including stigma and medical mistrust.

This section will also discuss health equity challenges for intersex adults. Intersex adults face many health care challenges, including that most health care professionals have not been offered training to meet intersex people’s lifespan health needs (Berry & Monro, 2022; Danon, 2018). Without access to the care they need, intersex people are often exposed to unnecessary health risks (e.g., incorrect medication dosages, denials for medically necessary treatments). Medical mistrust resulting from negative past health care experiences prevents many intersex people from even seeking important health care services and preventive screenings, increasing their risks of developing serious and potentially fatal health conditions including cancer and other chronic diseases (Charron et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022). Addressing these barriers is an important step in promoting promising practices for health equity.

Without access to the care they need, intersex people are often exposed to unnecessary health risks (e.g., incorrect medication dosages and denials for medically necessary treatments).

Health Equity for Intersex Infants and Children

Intersex variation is often identified in utero or at birth. New parents are often presented with unexpected and significant decisions about how to ensure the best medical care and outcomes for their child with limited information. Historic and current medical protocols often focused on immediate surgical interventions to conform a child’s sex characteristics to a single sex, not because such surgical interventions were medically necessary, but because of social and cultural expectations about how bodies should appear. However, a growing body of evidence and medical literature has documented the medical harms to intersex people across their lifespan resulting from childhood medical interventions performed when the child was too young to participate in significant medical decisions. Being unable to make these decisions for themselves exacerbates the medical mistrust that many intersex people report and further leads to barriers to care, health disparities, and worsened health outcomes among intersex adults.

“The doctors told us it was important to have the surgery right away because it would be traumatic for our child to grow up looking different. What’s more traumatic? This sort of operation or growing up a little different?”

Source: anonymous parent of intersex child as quoted in InterACT & Human Rights Watch, 2017

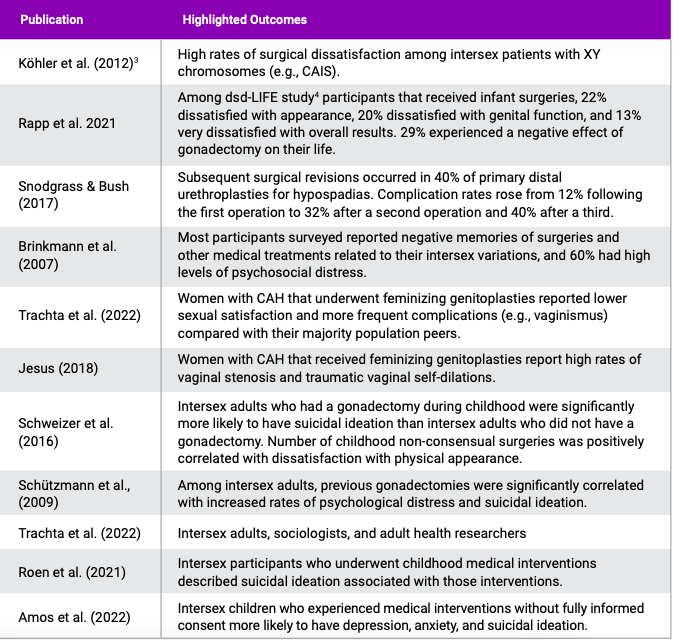

Growing Evidence of Harm

Multiple recent studies have examined outcomes, medical complications, and psychosocial impacts resulting from interventions performed on intersex individuals in infancy and early childhood—interventions not sought by the intersex patients themselves. These studies have associated these interventions with relatively high rates of dissatisfaction and health challenges later in life. Table 2 of the Appendix contains citations for the lasting and complex harms that can occur from early, nonconsensual interventions performed on intersex infants.

Prevalent complications of these interventions include significant scarring, loss of sexual function, urinary or vaginal complications, chronic pain, or early-onset osteoporosis. Qualitative evidence from people with lived intersex experience (see Table 2 as well as Baratz, 2016; Carmack et al., 2016; Elders et al., 2017; and others) affirms the medical harms that result from non-emergent, non-consensual procedures on intersex infants. The inability of intersex infants to participate in decision making further underscores the importance of training and resources for health care providers to ensure they are equipped to offer the best medical care and advice to intersex children and their families.

Parental Supports and Information Sharing

Misinformation and stigma regarding intersex variations makes it difficult for parents to prepare for the birth of an intersex child, which can cause significant post-traumatic stress, uncertainty, and fear for their child’s future (Charron et al., 2022; Pasterski et al., 2014; Rolston et al., 2015). Parents who are seeking to support the health and wellbeing of their intersex child often struggle to access accurate and affirming information, and may be encouraged by providers to seek medical interventions for their child that do not reflect the growing evidence that non- emergent nonconsensual surgical procedures on intersex youth can cause lasting harm.

Parents who are seeking to support the health and wellbeing of their intersex child often struggle to access accurate and affirming information.

(Magrite et al., 2022; A. Tamar-Mattis et al., 2014; Timmermans et al., 2018). While many health care providers work to support the health of their intersex patients, some current practices may make it harder for parents to make informed decisions about the health of their intersex infant or child. Practices include:

Encouraging treatment decisions based on societal views of sex and gender socialization even when such interventions may carry the risk of adverse health outcomes (Cannoot, 2021; Naezer et al., 2021; Timmermans et al., 2019).

Raising concerns that if a parent delays non-emergent medical interventions that an intersex child may be harmed (Baratz, 2016; Baratz & Feder, 2015; Magrite et al., 2022).

Not discussing treatment alternatives, particularly mental health and peer support to mitigate potential stigma (Charron et al., 2022; Magrite et al., 2022).

Overstating the risks of social stigma and potential “gender incongruence” versus complication risks associated with early intersex interventions (Hegarty et al., 2021; Timmermans et al., 2018).

Providing inadequate psychosocial support, particularly counseling for parents who may need additional support in learning to meet the needs of their intersex child (Baratz, 2016; Cannoot, 2021; Roen, 2019; A. Tamar-Mattis et al., 2014).

Encouraging interventions based on the assumption that most parents have insufficient “coping abilities” to raise a child with variations of sex characteristics (De Clercq & Streuli, 2019; Hegarty et al., 2021).

These practices can leave many families of intersex children feeling rushed and confused when making treatment decisions (Cannoot, 2021; De Clercq & Streuli, 2019).

Concealment of Intersex Status to Children

Historic approaches to intersex care emphasized the need to conceal children’s intersex status from the children themselves to avoid confusion and negative psychosocial outcomes (Griffiths, 2018; Meoded-Danon & Yanay, 2016; Reis, 2012). This concealment of intersex status included hiding the true reason for medical interventions. Some intersex people do not learn about their intersex variations or true reasons for medical interventions until adolescence or adulthood, creating additional feelings of anger and medical mistrust (Davis, 2015; Monro et al., 2017). This concealment can result in shame, depression, suicidal ideation for some individuals (Jones, 2022; Sani et al., 2020), and other mental health issues (Czyzselska, 2021; Hegarty, 2023; Rosenwohl-Mack et al., 2020; van de Grift & on behalf of dsd-LIFE, 2021).

Delaying Non-emergent Interventions

In contrast to practices noted above that encourage early surgical interventions for intersex children and concealment of medical history, health care providers and parents can work together to decide that it is in the best interest of the child to delay any non-emergent medical interventions until an intersex child is old enough to be involved in decision- making about their sexual and reproductive health. Absent a medical emergency, the health of intersex patients is most effectively advanced by delaying non-emergent interventions, preserving the ability of the intersex patient to participate

in decision-making about their care. Evidence shows that in these cases, intersex individuals face better long-term health outcomes (InterACT & Human Rights Watch, 2017; Reis, 2022; Schweizer et al., 2016).While early surgical interventions have been justified by the belief that children will have better outcomes if they do not grow up in bodies that others perceive as different or abnormal, multiple studies across intersex variations have shown that children who received these interventions will still often experience differences due to medical monitoring as well as the potential need for follow up surgeries and other challenges related to the interventions themselves (see examples in Table 2 of the Appendix).

Health care providers and parents can work together to decide that it is in the best interest of the child to delay any non-emergent medical interventions until an intersex child is old enough to be involved in decision- making about their sexual and reproductive health.

Health Equity for Intersex Adults

Intersex adults thrive in supportive communities with appropriate medical care. Yet, intersex adults face significant health care barriers during adulthood, including discrimination in health care when accessing services and failures in health care privacy. Intersex individuals also experience difficulty in health care surrounding major life events such as fertility and parenthood (Sanders et al., 2022; Słowikowska-Hilczer et al., 2017). Multiple recent studies and consensus statements (e.g., Charron et al. 2022; Cools et al. 2018; Flück et al. 2019) have highlighted the importance of lifespan approaches for health care for people with intersex variations, noting that health care needs change throughout life. These areas for growth in the development of lifespan health care approaches include monitoring potential side effects and complications from medical interventions, awareness of potential comorbidities, patient-centered reproductive and sexual health, and accessing affirming primary care providers.

“As an adult, it’s extraordinarily difficult to get health care. [...] Currently, I’m living in a major city but not getting adequate gynecological care related to health issues because the providers don’t know what to do with my anatomy. They simply bounce me to another provider or tell me they don’t know how to help. I’ve been denied medical testing because they did not know how to mark my sex without a date of last menstrual cycle or because I refused to take a pregnancy test after explaining that I have no uterus. These are just some of the few ways I’ve been denied adequate care.”

Source: input from anonymous intersex listening session participant

The lack of research on intersex adult health care needs (Berry & Monro, 2022; T. Jones, 2018) means that many intersex adults lack access to affirming health care. Presently there are few studies conducted on numerous crucial aspects of care that center the needs of intersex adults, including primary care, preventive screenings, quality of care, and care for older intersex

people as well as specialized care such as cancer screening, substance use, and behavioral risk factor research. As a result, intersex adults routinely receive inadequate care and experience significant barriers. In one qualitative study among intersex adults, 47.8 percent of participants reported delaying emergency health care and 65.4 percent reported delaying preventive health care due to prior negative experiences in health care. Similarly, the Pennsylvania Department of Health (2022) found that 62 percent of intersex respondents to the 2022 Pennsylvania LGBTQ Health Needs Assessment had experienced a negative reaction from a health care provider when they disclosed their intersex status, and 36 percent of intersex respondents said they fear seeking medical treatment.

62% of intersex respondents had experienced a negative reaction from a health care provider when they disclosed their intersex status.

At the same time, most medical record systems, treatment protocols, and insurance claim systems do not adequately account for intersex people (Albert & Delano, 2022; Davison et al., 2021; Keuroghlian, 2021).

These systems often lack the flexibility to reflect intersex variations, which can increase medical mistrust and contribute to treatment failures and hesitancy to disclose intersex status. By default, this results in incomplete medical records that pose health risks for intersex people.

Additionally, because of lack of adequate training for providers, health care workers, analytical laboratories, and health insurers may make assumptions about intersex patients that make it harder for them to access high-quality care. Those assumptions can include that a person’s sex or gender identity is congruent with their sex characteristics, or that sex-based differences (like hormonal profiles and anatomy) can only present in one of two ways rather than the actual multiplicity of biological variation. (Albert & Delano, 2022; Committee on Measuring Sex, Gender Identity, and Sexual Orientation et al., 2022).

Intersex people often experience negative interactions with primary care providers, hospital staff, and other health care workers, particularly once health care workers learn about their intersex variations or history of medical interventions (e.g., Alpert, Cichoskikelly, and Fox 2017; Prandelli 2021; Magallon and Swadhin 2022). Health care workers may also misattribute unrelated health problems to intersex variations or interventions related to them, thus potentially delaying or denying preventive screenings and medically-necessary treatments (Alpert et al., 2017; Charron et al., 2022). These negative health care experiences, including health care discrimination and denial of care, can result in intersex adults avoiding medical care, leading to poorer overall health and worse health outcomes.

Additionally, given the pervasiveness of negative past experiences that people with intersex variations have encountered in health care contexts, intersex people often report significant mistrust of health care (Wang et al., 2022). Although every intersex person’s experience may differ, medical mistrust often stems from:

The knowledge gap among clinicians about intersex variations;

Stigma and lack of affirming care in both pediatric and adult health care settings;

Experiences of loss of bodily autonomy resulting from medical interventions related to intersex characteristics; and

Concealment of medical information from the intersex person.

“I’ve had doctors write ‘ambiguous genitalia’ on the front of all of my charts. So when I get checked in or even go get my blood drawn, that’s the first thing everyone sees, and it determines how I get treated. They giggle at me, and I’ve had one person refuse to draw my blood before.”

Source: anonymous intersex person as quoted in InterACT & Human Rights Watch, 2017

Intersex people often experience negative interactions with primary care providers, hospital staff, and other health care workers. [...] These negative health care experiences, including health care discrimination and denial of care, can result in intersex adults avoiding medical care, leading to poorer overall health and worse health outcomes.

Challenges in Cancer Screenings and Care

Cancer continues to be a leading cause of death for all Americans. Preventive screening is key to improving cancer mortality and morbidity. Despite this, intersex adults experience disparities and discrimination regarding screenings and treatment for cancer (Power et al., 2022). The challenges stem from a lack of research and data collection on the specific needs of intersex patients. For example, radiation and medical imaging professionals are rarely trained about conducting proper examinations (e.g., positron emission tomography [PET] scans) or interpreting results for patients with intersex variations, which can lead to misdiagnoses and treatment denials (Pratt‐Chapman et al., 2023). Intersex people often are prevented from receiving preventive gonadal cancer screenings because screening protocols are developed with population-level data and screenings have not been developed for internal gonads (Tabaac et al., 2018).

“For health care in general, I just try not to go unless it’s an emergency.”

Source: intersex person as quoted in InterACT & Human Rights Watch, 2017

Further, structural barriers persist even when screening is recommended. Despite clear coverage rules and antidiscrimination protections in the Affordable Care Act, and even when physicians are fully aware of an intersex patient’s needs, medically necessary preventive screenings and treatments are often delayed, not offered, or not covered by insurance due to gaps within health records systems, treatment protocols, and insurance reimbursement models that presume a patient’s assigned sex at birth reflects their anatomy (Keuroghlian, 2021; Lau et al., 2020; Thompson, 2016).

Within cancer care, many intersex people avoid disclosing their status to oncologists and other health care professionals to avoid potential discrimination and negative health care experiences. Power et al., 2021, 2022

Finally, intersex people may not disclose or may be unaware of specific aspects of their variation. Within cancer care, many intersex people avoid disclosing their status to oncologists and other health care professionals to avoid potential discrimination and negative health care experiences. (Power et al., 2021, 2022). Intersex patients sometimes fear that they will be misgendered or have clinicians order tests and examinations unrelated to their cancer (Berry & Monro, 2022; Power et al., 2021, 2022). For example, most physicians follow clear screening recommendations for prostate cancer, which is often treatable if detected early. However, there are no common practices to check for the presence of a prostate in patients with a known or suspected intersex variation and to then notify the patient regarding their need to follow prostate cancer screening guidelines.

In studying the avoidance of preventive cancer screenings among intersex adults, the 2022 Pennsylvania LGBTQ Health Needs Assessment found that 12.9% of intersex respondents who were assigned female at birth and are within the recommended age range never had a cervical Pap test (Keuroghlian, 2021; Pennsylvania Department of Health, 2022). Delayed or avoided preventive screenings increase the risk of cancer mortality since the window for early detection may be missed.

Advancing Health Equity for Intersex Individuals Section 2: Barriers to Health Equity for Intersex Individuals | 9

Inadequate Sexual Health Care and Fertility Counseling

The sexual health of intersex people is impeded by inadequate public health research, and fertility care remains challenging for intersex people to access (Keuroghlian, 2021; Tordoff et al., 2022). Public health research on the prevalence and transmission of HIV and sexually transmitted infections often excludes or misclassifies intersex people to simplify study design (Albert & Delano, 2022; Tordoff et al., 2022), impeding intersex people from STI screening and prevention efforts and preventing public health surveillance from adequately assessing behavioral risk among intersex populations (Morrison et al., 2021).

Intersex people face similar barriers to fertility counseling and access to assisted reproductive technology (Sanders et al., 2022; Słowikowska-Hilczer et al., 2017). Among those who received fertility information, only 53 percent were satisfied with the way that fertility options were discussed. Infertility treatments may be particularly relevant to intersex people who underwent treatments and surgeries during childhood and adolescence (Campo-Engelstein et al., 2017; C. Jones, 2020). Furthermore, some intersex people may be unaware of their ability to have their own biological children or of available assisted reproductive technology options (Sanders et al., 2022).

“I never felt like I could tell the doctors how victimized I felt by these exams. I was eight when I started to realize something wasn’t right about them. But I was scared that I would die if I didn’t cooperate with the doctors. It was only as an adult that I understood that all those exams were for the doctors’ education, and not for my health. My trust in my doctors was broken: I was continually exposed and violated for their benefit1, and not my own.”

Source: Konrad Blair, as quoted in Davis, 2015

Trauma and Mental Health Disparities

Because of stigma and discrimination, intersex people experience significantly higher rates of mental health challenges compared to the non-intersex population, including:

Depression, anxiety, and other mood disorders (Bohet et al., 2019; Czyzselska, 2021; Engberg et al., 2017; Rosenwohl-Mack et al., 2020);

Internalized stigma and negative self-image (Hart & Shakespeare-Finch, 2022; Meyer-Bahlburg et al., 2016);

Trauma-related symptoms from previous intersex-related medical interventions and examinations (e.g., Czyzselska 2021; Khanna 2021; Meyer-Bahlburg et al. 2016); and

Suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and self-harm (de Vries et al., 2019; Lucassen et al., 2021; Schweizer et al., 2016).2

These mental health disparities are also exacerbated for intersex individuals due to

lower availability of psychosocial resources, including peer support groups (Amos et al., 2022; Lampalzer et al., 2021). Intersex people with intersectional identities, including intersex people of color and intersex people with disabilities, may face even greater health disparities due to the impact of multiple axes of oppression.

Many intersex adults who underwent childhood medical interventions may have experienced repeated genital examinations throughout childhood and into adulthood, which may increase their medical mistrust (Czyzselska, 2021; Flewelling et al., 2022; Meyer-Bahlburg et al., 2016). Many intersex adults delay or avoid seeking mental health support due to medical mistrust (Czyzselska, 2021; Meyer-Bahlburg et al., 2016). This mistrust and avoidance of care is exacerbated by the incorrect attribution by some health care workers of mental health conditions to intersex variation itself (e.g., Bohet et al. 2019; Engberg et al. 2017) rather than to stigma and trauma from previous medical interventions (Berry & Monro, 2022; Hart & Shakespeare-Finch, 2022), further underscoring the benefit of affirming, trained mental health providers in mitigating self-harm and suicide risk. To combat medical mistrust, training for the next generation of health care professionals must account for both the medical and interpersonal needs of intersex patients, especially young children. When intersex individuals receive appropriate and affirming social support and mental health care, they can thrive.

When intersex individuals receive appropriate and affirming social support and mental health care, they can thrive.

SECTION 3: PROMISING PRACTICES

While intersex children and adults face significant barriers to health equity, as discussed in Section 2 of this report, across the globe intersex advocates, family members, community leaders, and health care providers are identifying and implementing promising practices to improve health outcomes for intersex individuals. This section summarizes a number of those promising practices.

Intersex People in Public Health and Biomedical Research

Intersex people, their experiences, and their health needs should not be invisible from public health epidemiology, yet this often results from assumptions that sex characteristics occur in one of two distinct sets and remain constant throughout life (Albert & Delano, 2022; Dunham & Olson, 2016; Morrison et al., 2021). This perspective can lead to experimental or survey design factors that omit or misclassify intersex people from public health and biomedical research. Thus, it is essential to properly include intersex people in survey design.

Inclusive Survey Questions

Both the Gender Identity in U.S. Surveillance (GenIUSS) Group (2014) and the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) Committee on Measuring Sex, Gender Identity, and Sexual Orientation (2022) have developed recommendations for asking about variations of sex characteristics in health surveys. These reports offer sample questions:

“Have you ever been diagnosed by a medical doctor with an intersex condition or a ‘Difference of Sex Development’ or were you born with (or developed naturally in puberty) genitals, reproductive organs, and/or chromosomal patterns that do not fit standard definitions of male or female?”

2 “Some people are assigned male or female at birth but are born with sexual anatomy, reproductive organs, and/or chromosome patterns that do not fit the typical definition of male or female. This physical condition is known as intersex. Are you intersex?”

3 “Were you born with a variation in your physical sex characteristics? (This is sometimes called being intersex or having a difference in sex development, or DSD.)”

Both groups highlighted the importance of not including “intersex” as a third category when asking questions about a respondent’s sex, as many people with intersex variations identify as male and female and do not view intersex variation as a third, entirely distinct sex. The NASEM Committee on Measuring Sex, Gender Identity, and Sexual Orientation (2022) recommends using the first sample question (above) due to community guidance and feedback from people with intersex variations.

Pennsylvania is the only state to have included the intersex community in a population-based health needs assessment. The yes or no demographic question the Pennsylvania Department of Health (2022) used is:

“Do you have an intersex condition (variation of sex characteristics / difference of sex development?)”

Data Richness and Complexity in Experimental Designs

Sex characteristics influence numerous aspects of medical care, including recommended preventive screenings, treatment and care protocols, medication responses, and surgical and anesthesia procedures (Brenna, 2021; Gonzales & Ehrenfeld, 2018; Morrison et al., 2021). Thus, intersex people may have specific health needs in all these areas that can be addressed only through research. For example, little research has been conducted on general anesthesia protocols for people with intersex variations; instead, intersex patients are typically given formulations based on non-intersex patient protocols without consideration of how intersex people’s unique physiology may require adjustments of standard protocols (Brenna, 2021; Leslie et al., 2018).

Sex characteristics influence numerous aspects of medical care, including recommended preventive screenings, treatment and care protocols, medication responses, and surgical and anesthesia procedures.

Brenna, 2021; Gonzales & Ehrenfeld, 2018; Morrison et al., 2021

Lack of inclusion of intersex people in public health and epidemiological research lessens the ability of federal, state, and local public health agencies to assess the health needs of intersex people, monitor public health disparities, address health inequities, and assess the effectiveness of public health efforts (Baker et al., 2021; Morrison et al., 2021). For example, there is no federal, state, or local data regarding COVID-19 cases and vaccination rates among intersex people, who may already be at higher risk for serious complications from COVID-19, and who may experience greater vaccine hesitancy due to medical mistrust (The Fenway Institute, 2020). The lack of data may also limit what is known about the extent to which preventive health guidelines apply to intersex people whose specific circumstances may not be accurately accounted for in current health data systems.

Given the history of medical mistrust and trauma among this population, community- informed research is necessary to achieve an appropriate sample size and remove sampling biases and inaccurate assumptions (Morrison et al., 2021; S. Tamar-Mattis et al., 2018; Thompson, 2016). Community-informed research will be more likely to lead to higher response rates among intersex populations and lead to better health equity for intersex populations.

Organizational and International Developments

Growing awareness of the needs of the intersex community have led multiple professional medical associations and human rights organizations to formally recognize the importance of advancing health equity for intersex people, including by re-evaluating medical practices that may cause long-term harms and violations of bodily autonomy. Examples of organizations that have taken recent steps to address challenges faced by intersex individuals include:

• Joint Statement at the United Nations signed by more than 53 countries (United Nations Human Rights Council, 54th Session, 2023)

• American Academy of Family Physicians (American Academy of Family Physicians, 2023)

Advancing Health Equity for Intersex Individuals Section 3: Promising Practices to Advance Health Equity for Intersex People | 13

The 15th, 16th, and 17th U.S. Surgeons General (Elders et al., 2017)

Physicians for Human Rights (2017)

Updated Yogyakarta Principles (International Panel of Experts in International Human Rights Law, Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity, Gender Expression, and Sex Characteristics, 2017)

Health Professionals Advancing LGBTQI+ Equality (2016)

World Health Organization (Eliminating forced, coercive and otherwise involuntary sterilization, (2014)

UN Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment (Juan E. Menez 2013)

Growing awareness of the needs of the intersex community have led multiple professional medical associations and human rights organizations to formally recognize the importance of advancing health equity for intersex people.

In addition, the federal government has taken important steps under the Biden-Harris Administration to strengthen protections and support for intersex individuals. For example, The U.S. Agency for International Development’s (USAID) 2023 LGBTQI+ Inclusive Development Policy states that non-emergent procedures

on intersex children “not only further social stigmatization of intersex individuals but can also lead to long- lasting medical complications and mental health impacts” (U.S. Agency for International Development, 2023). In addition, the Departments of Health and Human Services and Education have proposed rules that would strengthen non-discrimination protections for intersex individuals in federally funded health care, family planning, and education programs.

Approaches to Care Sensitive to Prior Trauma

Health care workers are often unaware of the trauma experienced by many intersex people, which can lead to intersex patients mistakenly being viewed as “combative” (National LGBT Health Education Center, 2020; Reis & McCarthy, 2016). For example, many intersex people have been forced to undergo invasive and unnecessary genital examinations throughout their lives (Crameri et al., 2015; Meyer-Bahlburg et al., 2016), so routine preventive screenings such as cervical Pap tests can be retraumatizing (Indig et al., 2021; National LGBT Health Education Center,

2020). In these cases, clinicians can help avoid retraumatizing the patient by (1) asking permission before performing the examination; (2) ensuring patient privacy, including from other health care personnel present for training purposes, and (3) suggesting an alternative such as a self-swab if the patient expresses discomfort with the examination (Ittelson et al., 2018; National LGBT Health Education Center, 2020). These types of practices promote respect for intersex patients and improve health care outcomes across the lifespan.

Shared decision- making necessitates understanding sex variations as a natural component of human diversity and prioritizing the needs of the intersex patient, rather than their caregivers.

(Crocetti et al., 2021; Ittelson et al., 2018; Monro et al., 2017)

Patient-Centered Care and Shared Decision-Making

Like all patients, intersex people should be able to make decisions about their own bodies and medical care. Yet many intersex people have not been able to do so.

Improving health equity for intersex people involves recognizing the importance of shared decision-making about care decisions throughout the healthcare process (Crameri et al., 2015; The Fenway Institute, 2020). Shared decision-making necessitates understanding sex variations as a natural component of human diversity (Crocetti et al., 2021; Ittelson et al., 2018; Monro et al., 2017) and prioritizing the needs of the intersex patient, rather than their caregivers.

Intersex-Specific Cultural Awareness

Intersex people face barriers to care due to a knowledge gap among health care workers regarding intersex variation. Even when health care professionals are trained in patient health care needs related to sexual orientation and gender identity, this training may not always cover intersex people’s unique needs or barriers to care, leaving many health care professionals less knowledgeable about intersex issues compared to lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender health needs (Liang et al., 2017). Many health care professionals may also believe that intersex variation is primarily a pediatric concern and are thus unprepared when encountering an intersex adult patient (Alpert et al., 2017; Reis & McCarthy, 2016).

Multiple scholars (e.g., Alpert, Cichoskikelly, and Fox 2017; J. J. Liang et al. 2017; Mukerjee 2021) recommend intersex-specific cultural competency training on different intersex variations, histories of medical mistrust, and promising practices for culturally-affirming treatment. McDowell et al. (2020) outline several approaches for creating more affirming care for intersex people, including continuing education for health care workers.

Inclusive Communication

Health care workers may unintentionally exacerbate medical mistrust and lead to delayed or avoided care by using language that does not affirm their intersex patients (National LGBT Health Education Center, 2020; Reis & McCarthy, 2016). Intersex people are also routinely asked invasive and unnecessary questions that are unrelated to their current health concerns (Alpert et al., 2017; Ittelson et al., 2018). Examples of current areas for growth include:

Health care continues to use diagnosis-based (DSD) language rather than the terms patients use to describe themselves and their body parts (National LGBT Health Education Center, 2020).

Many electronic health record systems do not adequately record patient’s chosen name, pronouns, and gender identity (National LGBT Health Education Center, 2020; Thompson, 2016).

“Ask us what we need. Give us plenty of time during appointments. Hear our pain. Give us hope. Treat us with respect.”

Source: Jay Kyle Peterson, as quoted in Davis, 2015

Many intersex people report being asked invasive questions unrelated to their current health needs (Alpert et al., 2017; Thompson, 2016).

Many clinical intake forms are restrictive with regard to sex fields, preventing intersex patients from accurately completing these forms (Keuroghlian, 2021; Pratt-Chapman et al., 2022; Thompson, 2016).

Informed consent is not always used with intersex patients during treatment, including when providers seek permission to touch or view intimate body parts (Alpert et al., 2017; National LGBT Health Education Center, 2020).

Disclosure of the patient’s assigned sex at birth and intersex variations are not always limited to a need- to-know basis within a clinic or health network (Funk et al., 2019; Thompson, 2016).

Strengthening Nondiscrimination Protections

Many hospitals do not explicitly include sex characteristics in the clinic or hospital’s patient nondiscrimination policy (Ittelson et al., 2018). Health care providers can advance health equity for intersex patients by ensuring that patient nondiscrimination policies explicitly include protections against discrimination based on intersex status or variations in sex characteristics. Health care providers can also ensure that information about intersex status is fully protected in patient privacy procedures.

Incorporating Sociocultural Factors into Care

Patients benefit when clinicians and other healthcare professionals account for historical sociocultural influences on the health and well-being of intersex people, including physical and psychological impacts of previous medical interventions, stigma, discrimination, and medical mistrust (Crameri et al., 2015; Czyzselska, 2021; Indig et al., 2021). Adopting an approach of “treating everyone the same” may ignore the specific or unique elements of intersex people’s health needs and thus perpetuate and exacerbate health disparities (Alpert et al., 2017; Crameri et al., 2015). For example, intersex older adults may be less likely to see new physicians or specialists based on fear of mistreatment or discrimination (Indig et al., 2021).

Family Acceptance and Social Support

Parental acceptance of a child’s intersex variation can significantly reduce the risk of mental health distress, and suicidal ideation among intersex people (Schweizer et al., 2016). Similarly, peer support, including intersex support and community groups, can significantly improve mental health outcomes and build mental health resilience (Henningham & Jones, 2021; T. Jones, 2016; Schweizer et al., 2016).

Multiple recent studies have illustrated that openness about intersex variation can result in more positive psychological outcomes, including reduced depression, feelings of shame, and isolation (e.g., Davis and Wakefield 2017; van de Grift and on behalf of dsd-LIFE 2021; Hart and Shakespeare-Finch 2022). Jones (2017) demonstrated through a survey of 272 people with intersex variations that the acceptance of intersex variation significantly impacts family dynamics, and intersex participants wanted their families to embrace them for who they are, provide more information on their variations, and help them to access affirming care.

“Finding a support group was the best thing that ever happened to me. I discovered joy and happiness in finding and being surrounded by my own [people], my own brethren; the many who had undergone similar or worse circumstances than myself gave me a feeling of standing my ground and holding my head high. My sister eventually became involved with the support group as well. It’s been a long journey, but I can finally say I no longer feel shame for being an intersex individual.”

Source: Diana Garcia, as quoted in Davis, 2015

Self-Acceptance Regarding Intersex Variation

Self-acceptance and discussions about intersex variations can also enable many intersex adolescents and adults to appreciate their body, improving overall self-acceptance and mental health (Davis & Wakefield, 2017; Sanders et al., 2021; van de Grift & on behalf of dsd-LIFE, 2021). Van de Grift et al. (2021) also recommend that health care professionals (including mental health providers) assist patients with intersex variations in deciding the level of disclosure, including when and to whom. For intersex people with traumatic experiences, self-acceptance can play an important role in posttraumatic growth and recovery (Hart & Shakespeare-Finch, 2022).

SECTION 4: GUIDING PRINCIPLES FOR ACTION

Intersex individuals face significant barriers to accessing the health care they need. As highlighted throughout this report, the lack of awareness about the health needs and outcomes of intersex children and adults is exacerbated by a lack of appropriate training and expertise among health care professionals to best serve this population. As a result, many intersex individuals struggle to access affirming and competent health care, which exacerbates health disparities and contributes to medical mistrust and avoidance of care. Every person should be able to achieve the highest level of their health, in alignment with HHS Healthy People 2030 goals, and every person deserves to make medical decisions about their own body.

Advancing health equity for intersex individuals will require a whole-of-society approach, including from policymakers, health care providers, educators, researchers, parents, families, and community members.

Below, we offer guiding principles for the whole-of-society to improve health outcomes for intersex individuals.

1 Protect the civil rights of intersex people, affirm the role of parents in supporting their intersex children, and promote bodily autonomy and informed consent as guiding principles for all health policies, including by ensuring all non-emergent care is guided by the express wishes of the intersex individual themselves.

Even as we acknowledge the limitations of current research, sufficient evidence exists to conclude that there are well-documented medical harms to intersex people across their lifespan resulting from childhood medical interventions performed when the child was too young to participate in decision-making. The loss of the ability to consent to early surgical interventions can be a primary factor in the medical mistrust that leads to barriers to care, health disparities, and worsened health outcomes among intersex adults. The path forward to improving health equity for intersex people centers respect for intersex bodily autonomy and affirms the role of parents in supporting their intersex children.

2 Continue to build the evidence to develop intersex-affirming standards of care for the clinical treatment of intersex people across their lifespan.

In addition to the promising practices noted above, there is more work to do to identify ways to improve the health and well-being of intersex adults. More evidence-based research and analysis is needed to ensure intersex adults will no longer face challenges finding health care providers who understand their unique medical needs, including those related to managing previous medical interventions, fertility, and aging.

3 Welcome and acknowledge intersex people and their unique health needs across their lifespan in routine preventive and primary care visits to build patient-provider trust.

Intersex-affirming care should be available in all medical subspecialties. Building trust is essential to allow for improved whole life outcomes, which can help to reverse existing trends in disparities, delay of necessary screenings, and other health care avoidance.

4 Promote promising practices among health care professionals to prioritize access to care and quality of care for intersex patients.

Intersex variations are a natural component of human physical diversity. Advancing health equity for the intersex community will require health care professionals to center the lived experience of intersex people, including by harnessing opportunities for intersex-affirming research and training to advance evidence-based care in all treatment realms.

5 Promote family acceptance for intersex youth.

Family support is critical to the mental and physical health of all youth, including intersex youth. Those interfacing with intersex youth, including health care providers, should prioritize and model intersex-affirming approaches and provide resources and pathways toward peer support to help ensure intersex children can be celebrated.

6 Improve access to competent and affirming mental health services for intersex people.

Many intersex people struggle with the mental health effects of negative past health care and societal experiences, and there is a significant knowledge gap among mental health providers regarding intersex people and the specific health issues they face. Listening to the voices of intersex people in prioritizing affirming mental health care will help ensure this community is able to thrive.

7 Develop an intersex-affirming federal research agenda that informs policy interventions to improve health outcomes for intersex people.

More research is needed on the lifespan health needs of intersex adults. Robust data is needed to evaluate the efficacy of different medical and mental health interventions for intersex adults. By centering intersex community-informed research based on the needs and goals of the intersex population, new research can help inform policy and practices that improve health and well-being.

8 Address insurance coverage and medical record challenges impacting intersex adults.

Medical records and coding systems, coupled with reimbursement policy, often are unable to account for intersex variations and as a result, intersex patients report numerous challenges accessing insurance coverage for necessary medications and health care services. Systems-wide improvements that reflect the reality of intersex variations will improve health care outcomes, increase access, and reduce stigma.

9 Expand data collection on the health and well-being of intersex people across their lifespan.

Most federal, state, and institutional data collection efforts that measure demographic disparities do not collect data on the intersex community. Collecting and reporting intersex demographics and informatics is essential to improving our understanding of intersex people and their health challenges in a way that improves outcomes for this community.

10 Partner with trusted intersex-affirming community-based and national organizations to engage in community-level health promotion.

Community-based organizations can be key partners in designing research as well as trusted messengers for health promotion efforts to historically excluded communities, including intersex individuals. By partnering with intersex-led and intersex-affirming groups, researchers and those advancing public efforts can ensure their efforts properly reflect the needs of the impacted community.

11 Include people with lived intersex experience in every effort to implement these recommendations.

Attentiveness to the experiences, health disparities, traumas, and successes of individuals with diverse lived intersex experiences is essential throughout the process to develop and implement comprehensive intersex-affirming health policy and practices.

APPENDIX 1

METHODOLOGY

OASH led a comprehensive, mixed-methods data collection process to survey the state of intersex health and to develop recommendations for improved access to care and health outcomes. Across all its activities, OASH adopted a lifespan approach to its exploration of intersex health, focusing not only on early-life diagnoses of intersex individuals but on approaches that could compromise or support lifelong outcomes in all health domains—from primary and preventive care to mental health and cancer care.

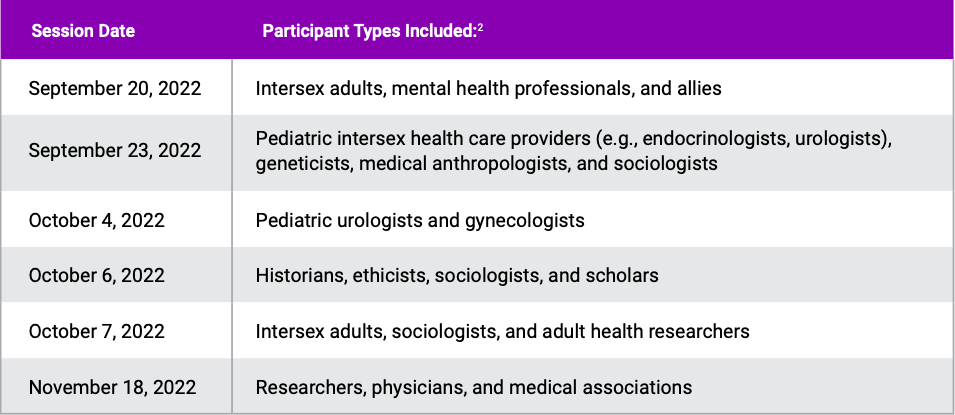

OASH coordinated six listening sessions between September 20 and November 18, 2022. These listening sessions convened intersex individuals, parents, researchers, and health care workers to discuss intersex health challenges, including research gaps, clinical experiences, medical mistrust, health education, and policy gaps. OASH also published an RFI in the Federal Register and invited public comment on promising practices to advance health equity for intersex individuals. Simultaneously, OASH launched a scoping review of relevant published literature.

Listening Sessions

OASH conducted six listening sessions, as shown in Table 1 below:

Table 1: Dates and participants of OASH listening sessions regarding intersex health equity.

OASH adopted a lifespan approach to its exploration of intersex health, focusing not only on early-life diagnoses of intersex individuals but on approaches that could compromise or support lifelong outcomes in all health domains.

Questions for Listening Sessions

For the first five listening sessions (i.e., September 20, 2022 – October 7, 2022), participants were asked two questions to initiate larger discussions about intersex health needs, care gaps, and research:

What are the current gaps in research, clinical practice, and policy that should be addressed in the final report?

Are there innovative types of research, clinical practices, and policies that should be highlighted in the final report?

The sixth listening session on November 18, 2022, focused on research gaps and needs; thus, participants were asked five questions:

What are the most critical research opportunities in pediatric and young adult intersex health?

What are the most critical research opportunities in adult intersex health?

What are the most critical systems-related (health services research, policy, etc.) research opportunities?

What are the barriers to conducting intersex-related research?

Are there any other recommendations for the final report?

Although not explicitly asked by organizers, many participants had individual opinions and recommendations for the content of the report itself, including sections to include, and attendees for upcoming listening sessions. For example, most intersex participants emphasized that the report should recognize variation of sex characteristics as a natural component of human diversity rather than a medical disorder. Principal themes identified from these listening sessions are described in Section 4.

Scoping Review

A scoping review was conducted based upon agreed-upon research questions using the scoping review approach outlined in Arksey and O’Malley (2005). Based upon themes identified during the listening sessions, OASH used the following list of research questions:

Are there promising practices for the promotion of health/advancement of health equity among the intersex patient population?

How have historical views of variation of sex characteristics affected current medical and psychosocial care for intersex people?

How do views on gender identity and sexual orientation inform medical practices and attitudes regarding health care and treatment decisions for intersex people?

What are potential medical complication risks from surgeries on intersex infants and young children?

How have changes in terminology (e.g., intersex, disorders/differences of sex development [DSD]) influenced medical and societal views on intersex variation?

What studies are available on current health practices for intersex adults?

Is there evidence of health disparities, including reduced preventive care (e.g., cancer screenings), among intersex adults?

What research exists on discrimination against intersex people outside of the medical environment?

What research exists on factors (e.g., familial support, psychological resilience) that support well- being in and positive psychosocial outcomes in intersex people?

What are the indications of medical mistrust among intersex adults?

Is there evidence of increased prevalence of high-risk behaviors among intersex adults compared to the general population?

What are the published critiques of research on variations in sex characteristics and health outcomes in intersex people?

How does misclassification or omission of variations in sex characteristics and intersex identity impact biomedical and sociological research?

Relevant Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Based upon the questions above, OASH led a review of current (2017 or later) peer-reviewed literature. Most literature included were primary studies and analyses of longitudinal cohort data. The scoping review identified secondary sources and scoping reviews, as many of the latter also include (1) recommendations for clinical

or psychosocial care (e.g., Indig et al. 2021; Zeeman and Aranda 2020); (2) comparisons of intersex care with health care approaches for other marginalized groups (Kirjava, 2022; Naezer et al., 2021); (3) critiques of previous research (T. Jones, 2018; Roen, 2019); and (4) recommendations for including intersex variation in public health research (Fraser, 2018; Tordoff et al., 2022).To focus the scoping review on adult care, including adolescence and transitions to adulthood, studies were excluded if they solely examined pediatric outcomes; however, studies on childhood surgeries that addressed outcomes among adults were included in this review. Studies were also excluded if they stated that they studied “LGBTQI+” people and education but the studies did not include any intersex participants or intersex- specific issues (Pratt-Chapman et al., 2022).

Some sources published prior to 2017 were included if they are frequently cited by current literature (e.g., Creighton et al. 2002), establish current care frameworks (e.g., Hughes et al. 2006), or were historical reviews frequently cited by current studies (e.g., Reis 2012). The scoping review ultimately included 167 sources. Sources published in 2017 or later account for approximately 87% of total publications included.

Request for Information in the Federal Register

To gain additional input and feedback from a range of stakeholders, OASH published an RFI on promising practices for advancing health equity for intersex individuals as a Federal Register Notice (FRN) (Volume 88. No. 28) on February 8, 2023. This RFI sought feedback from the scientific research community, clinical practice communities, intersex individuals and their families, scientific or professional organizations, federal partners, and other interested constituents. The RFI included two questions for respondents:

What do you see as the current clinical, research, or policy gaps that you are hoping this report addresses?

What recent or ongoing research, innovative clinical approaches, or policy actions do you think are important for us to know about as we begin this work?

The RFI was open for responses for four weeks and closed on March 13, 2023. Responses were reviewed by OASH staff, and inputs from these responses were used to inform the content of this report. A total of 53 comments were received, including from people with lived intersex experience, parents and caregivers of intersex individuals, health care workers, civil society, and professional medical associations.

APPENDIX 2: SELECTED EXAMPLES OF MEDICAL COMPLICATIONS AND PSYCHOSOCIAL OUTCOMES IN RECENT STUDIES

Although this study is from 2012, its results are frequently cited by more recent publications (e.g., Kreukels et al. 2019; Thyen et al. 2018). However, these publications often frame these complications as a result of intersex variations themselves and focus more on comparing complication rates between different forms of intersex variation.

-

REFERENCES

Albert, K., & Delano, M. (2022). Sex trouble: Sex/gender slippage, sex confusion, and sex obsession in machine learning using electronic health records. Patterns, 3(8), 100534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patter.2022.100534

Alpert, A. B., Cichoskikelly, E. M., & Fox, A. D. (2017). What Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, and Intersex Patients Say Doctors Should Know and Do: A Qualitative Study. Journal of Homosexuality, 64(10), 1368–1389. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2017.1321376

American Academy of Family Physicians. (2023). Genital Surgeries in Intersex Children. https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/genital-surgeries.html

Amos, N., Hart, B., Hill, A. O., Melendez-Torres, G. J., McNair, R., Carman, M., Lyons, A., & Bourne, A. (2022). Health intervention experiences and associated mental health outcomes in a sample of LGBTQ people with intersex variations in Australia. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 1–14.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2022.2102677

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32.

Baker, K. E., Streed, C. G., & Durso, L. E. (2021). Ensuring That LGBTQI+ People Count—Collecting Data on Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity, and Intersex Status. New England Journal of Medicine, 384(13), 1184–1186. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2032447

Baratz, A. B. (2016). Re: “Surgery in disorders of sex development (DSD) with a gender issue: If (why), when, and how?” Journal of Pediatric Urology, 12(6), 442–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpurol.2016.07.013

Baratz, A. B., & Feder, E. K. (2015). Misrepresentation of Evidence Favoring Early Normalizing Surgery for Atypical Sex Anatomies. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(7), 1761–1763. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0529-x

Berry, A. W., & Monro, S. (2022). Ageing in obscurity: A critical literature review regarding older intersex people. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters, 30(1), 2136027. https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2022.2136027

Bohet, M., Besson, R., Jardri, R., Manouvrier, S., Catteau-Jonard, S., Cartigny, M., Aubry, E., Leroy, C., Frochisse, C., & Medjkane, F. (2019). Mental health status of individuals with sexual development disorders: A review. Journal of Pediatric Urology, 15(4), 356–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpurol.2019.04.010

Brenna, C. T. A. (2021). Limits of mice and men: Underrepresenting female and intersex patients in anaesthesia research. Trends in Anaesthesia and Critical Care, 37, 2–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tacc.2021.01.001

Brinkmann, L., Schuetzmann, K., & Richter-Appelt, H. (2007). ORIGINAL RESEARCH—INTERSEX AND GENDER IDENTITY DISORDERS: Gender Assignment and Medical History of Individuals with Different Forms of Intersexuality: Evaluation of Medical Records and the Patients’ Perspective. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 4(4), 964–980. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00524.x

Campo-Engelstein, L., Chen, D., Baratz, A. B., Johnson, E. K., & Finlayson, C. (2017). The Ethics of Fertility Preservation for Pediatric Patients With Differences (Disorders) of Sex Development. Journal of the Endocrine Society, 1(6), 638–645. https://doi.org/10.1210/js.2017-00110

Cannoot, P. (2021). Do parents really know best? Informed consent to sex assigning and ‘normalising’ treatment of minors with variations of sex characteristics. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 23(4), 564–578. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2020.1785012

Carmack, A., Notini, L., & Earp, B. D. (2016). Should Surgery for Hypospadias Be Performed Before An Age of Consent? The Journal of Sex Research, 53(8), 1047–1058. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2015.1066745

Advancing Health Equity for Intersex Individuals References | 19

Carpenter, M. (2018). Intersex Variations, Human Rights, and the International Classification of Diseases. Health and Human Rights, 20(2), 205–214.

Charron, M., Saulnier, K., Palmour, N., Gallois, H., & Joly, Y. (2022). Intersex Stigma and Discrimination: Effects on Patient-Centred Care and Medical Communication. Canadian Journal of Bioethics, 5(2), 16. https://doi.org/10.7202/1089782ar

Committee on Measuring Sex, Gender Identity, and Sexual Orientation, Committee on National Statistics, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education, & National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2022). Measuring Sex, Gender Identity, and Sexual Orientation (N. Bates, M. Chin, & T. Becker, Eds.; p. 26424). National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26424

Cools, M., Nordenström, A., Robeva, R., Hall, J., Westerveld, P., Flück, C., Köhler, B., Berra, M., Springer, A., Schweizer, K., Pasterski, V., & on behalf of the COST Action BM1303 working group 1. (2018). Caring for individuals with a difference of sex development (DSD): A Consensus Statement. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 14(7), 415–429. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-018-0010-8

Crameri, P., Barrett, C., Latham, J., & Whyte, C. (2015). It is more than sex and clothes: Culturally safe services for older lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex people: It is more than sex and clothes. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 34, 21–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajag.12270

Creighton, S. M., Alderson, J., Brown, S., & Minto, C. L. (2002). Medical photography: Ethics, consent, and the intersex patient. BJU International, 89, 67–72.

Crocetti, D., Monro, S., Vecchietti, V., & Yeadon-Lee, T. (2021). Towards an agency-based model of intersex, variations of sex characteristics (VSC) and DSD/dsd health. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 23(4), 500–515. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2020.1825815

Czyzselska, J. (2021). The truth that’s denied: Psychotherapy with LGBTIQ+ clients who identify as intersex. Psychology of Sexualities Review, 12(1), 20–33. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpssex.2021.12.1.20

Danon, L. M. (2018). Time matters for intersex bodies: Between socio-medical time and somatic time. Social Science & Medicine, 208, 89–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.05.019

Davis, G. (2015). Normalizing Intersex: The Transformative Power of Stories. Narrative Inquiry in Bioethics, 5(2), 87–89. https://doi.org/10.1353/nib.2015.0046

Davis, G., & Wakefield, C. (2017). The Intersex Kids are All Right? Diagnosis Disclosure and the Experiences of Intersex Youth. In P. Neff Claster, S. Lee Blair, & L. E. Bass (Eds.), Sociological Studies of Children and Youth (Vol. 23, pp. 43–65). Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1537-466120170000023004

Davison, K., Queen, R., Lau, F., & Antonio, M. (2021). Culturally Competent Gender, Sex, and Sexual Orientation Information Practices and Electronic Health Records: Rapid Review. JMIR Medical Informatics, 9(2), e25467. https://doi.org/10.2196/25467

De Clercq, E., & Streuli, J. (2019). Special Parents for “Special” Children? The Narratives of Health Care Providers and Parents of Intersex Children. Narrative Inquiry in Bioethics, 9(2), 133–147. https://doi.org/10.1353/nib.2019.0026

de Vries, A. L. C., Roehle, R., Marshall, L., Frisén, L., van de Grift, T. C., Kreukels, B. P. C., Bouvattier, C., Köhler, B., Thyen, U., Nordenström, A., Rapp, M., Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., & dsd-LIFE Group. (2019). Mental Health of a Large Group of Adults With Disorders of Sex Development in Six European Countries. Psychosomatic Medicine, 81(7), 629–640. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000718

Dunham, Y., & Olson, K. R. (2016). Beyond Discrete Categories: Studying Multiracial, Intersex, and Transgender Children Will Strengthen Basic Developmental Science. Journal of Cognition and Development, 17(4), 642–665. https://doi.org/10.1080/15248372.2016.1195388

Elders, M. J., Satcher, D., & Carmona, R. (2017). Re-thinking genital surgeries on intersex infants (Blueprints for Sound Public Policy). Palm Center.

Advancing Health Equity for Intersex Individuals References | 20

Engberg, H., Strandqvist, A., Nordenström, A., Butwicka, A., Nordenskjöld, A., Hirschberg, A. L., & Frisén, L. (2017). Increased psychiatric morbidity in women with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome or complete gonadal dysgenesis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 101, 122–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.08.009

Fausto-Sterling, A. (1993). The five sexes. The Sciences, 33(2), 20–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2326-1951.1993.tb03081.x

Flewelling, K. D., De Jesus Ayala, S., Chan, Y.-M., Chen, D., Daswani, S., Hansen–Moore, J., Rama Jayanthi, V., Kapa, H. M., Nahata, L., Papadakis, J. L., Pratt, K., Rausch, J. R., Umbaugh, H., Vemulakonda, V., Crerand, C. E., Tishelman, A. C., & Buchanan, C. L. (2022). Surgical experiences in adolescents and young adults with differences of sex development: A qualitative examination. Journal of Pediatric Urology, 18(3), 353. e1-353.e10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpurol.2022.02.028

Flück, C., Nordenström, A., Ahmed, S. F., Ali, S. R., Berra, M., Hall, J., Köhler, B., Pasterski, V., Robeva, R., Schweizer, K., Springer, A., Westerveld, P., Hiort, O., Cools, M., & __. (2019). Standardised data collection for clinical follow-up and assessment of outcomes in differences of sex development (DSD): Recommendations from the COST action DSDnet. European Journal of Endocrinology, 181(5), 545–564. https://doi.org/10.1530/EJE-19-0363

Fraser, G. (2018). Evaluating inclusive gender identity measures for use in quantitative psychological research. Psychology & Sexuality, 9(4), 343–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2018.1497693